Suggested Donation Levels

What have you learned?

Sinclair Single Trace Oscilloscope SC110, probably 1979 or 1980

Sinclair Electronics produced this machine during a time of change for the company. Clive Sinclair resigned in July 1979, and in September, the National Enterprise Board (NEB) took a 73% stake. They renamed the company Thandar Electronics in January 1980. The oscilloscope has the original name, its manual the new one.

Engineers use oscilloscopes to measure electrical phenomena and quickly test, verify, and debug their circuit designs. To keep it portable, the oscilloscope is powered by either AC mains power or batteries. Its 4cm screen was also used on Sinclair's Microvision pocket TVs.

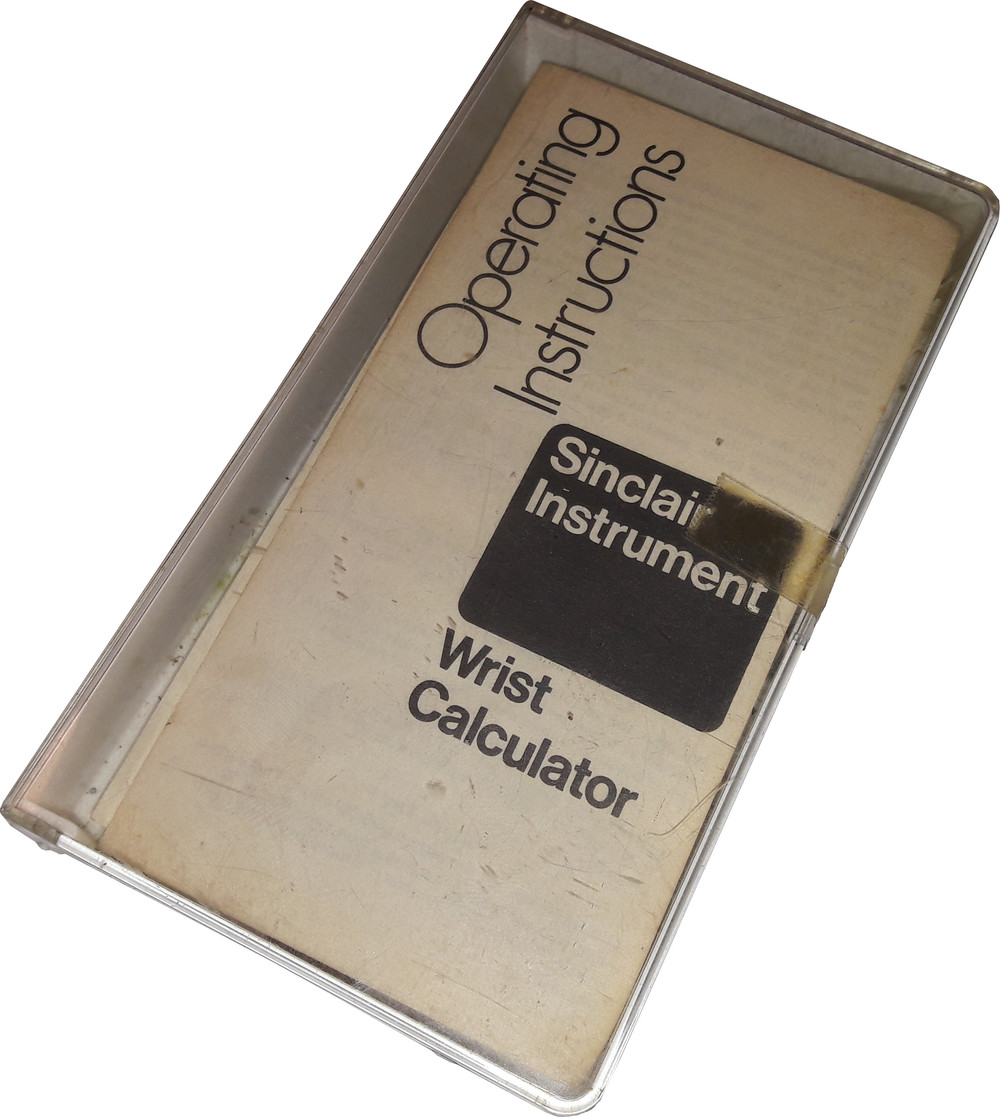

Sinclair Instrument Wrist Calculator, February 1977

This wrist calculator was sold as a kit, costing £9.95. A three-position button provided access to memory and square root functions.

Although futuristic, the wearable tech was beset by problems. Running on six hearing-aid batteries, these only lasted about 90 minutes and you then had to disassemble the unit to change them. The calculator was also unreliable. Unsurprisingly, sales were poor, and many of the units purchased were returned.

The calculator was produced by Sinclair Instrument, a parallel company to Sinclair Radionics.

Sinclair Digital Multimeter PDM35, 1977

The Sinclair PDM35 digital multimeter is a compact, portable, digital multimeter. It measures AC and DC voltage, DC current, and resistance. The LED display reads up to 1999. It uses the same case as the Sinclair Oxford calculator.

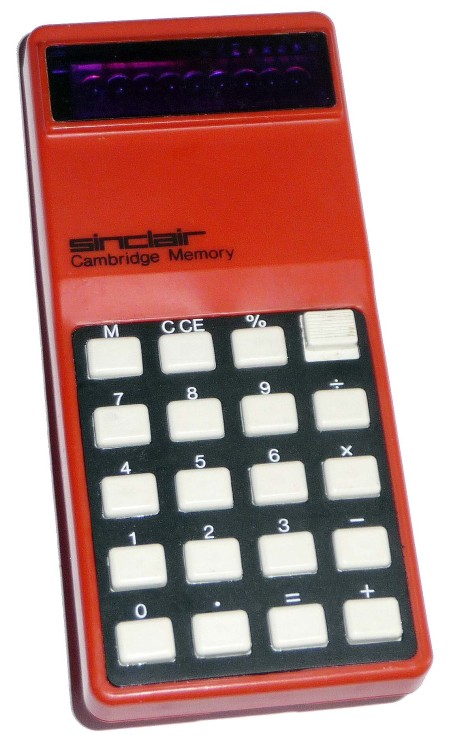

Sinclair Cambridge Calculator (Type 3), 1975

The Sinclair Cambridge series of calculators represented Sinclair's desire to make electronics more personal and portable. Introduced in Summer 1973 it was the second calculator from Sinclair Radionics, after the 1972 Executive. The Sinclair Cambridge was truly pocket-sized. The red plastic case with white keys hinted at the company's eye for design.

While the Type 1 and 2 took AAA batteries, this Type 3 took a larger PPP3 battery giving it a bulge and duly dubbed the "pregnant model".

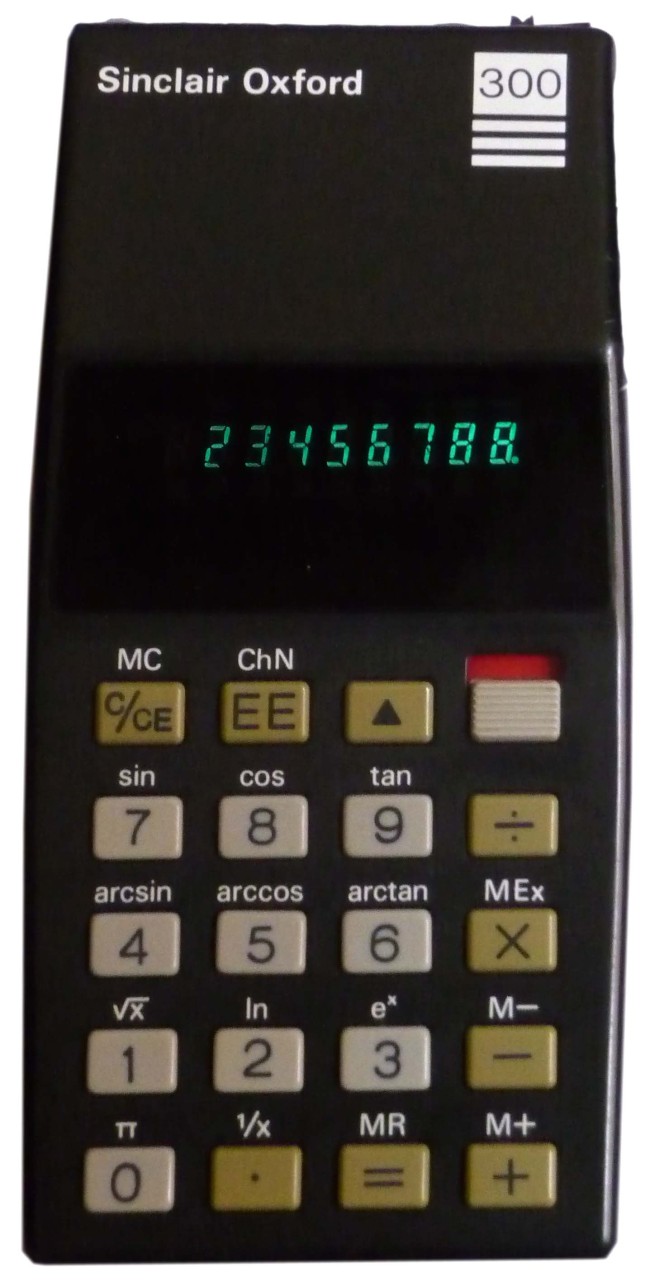

Sinclair Oxford 300 (Type 2), 1975

When Gillette was looking to enter the personal electronic business they turned to Sinclair Radionics, tasking them to build a pocket calculator. The result was the Gillette GPA. It was short-lived, but Sinclair released the calculator as the Sinclair Oxford. The 100, 200 and 300 were released simultaneously, each with different functionality. The 300 retailed for £29.95.

Sinclair Microquartz digital car clock, 1977

The Sinclair Microquartz was a digital car clock released in 1977. It was developed to use the parts from the unsuccessful Black Watch including the LED display and circuitry.

A button needed to be pressed to show the time, a little precarious if driving. However, it was more successful technically and commercially than the Black Watch.

Unlike most Sinclair products of the time, it could only be bought pre-built.

Flat Screen Pocket TV, 1983

The Sinclair TV80, also known as the Flat Screen Pocket TV or FTV1 was a commercial disappointment. The 15,000 sold failed to recoup the £4 million it cost to develop.

Like many of Sinclair's products it was technically advanced. Unlike earlier attempts at a portable television, the TV80 used a flat Cathode Ray Tube (CRT) with a side-mounted electron gun instead of a conventional CRT. The picture was made to appear larger by the use of a Fresnel lens.

Sinclair Black Watch Kit, 1985

The Black Digital Watch was a remarkable idea, but technically flawed. Its sleek design demonstrated Sinclair's interest in creating innovative tech which looked beautiful. A sleek black design was punctuated by the red LED display.

The marketing campaign claimed there was 'nothing to go wrong' but the watch was riddled with problems.

It only displayed the time when the hidden button was pressed. This drained the battery quickly, despite adverts claiming it would last for a year. The watch was also susceptible to static, which made the display freeze on one very bright digit, causing the batteries to drain even faster. Overheating was also a problem.

Launched in September 1975 by Sinclair Radionics, the Black Watch cost £24.95 ready-built or £17.95 as a kit.

So many were returned it made a huge loss. Sinclair would have been bankrupted had the National Enterprise Board not stepped in to inject money into the company.

Video: Black Watch Advert

Image 1: Black Watch Kit

Image 2: A rare white version of the watch (CH 66646)

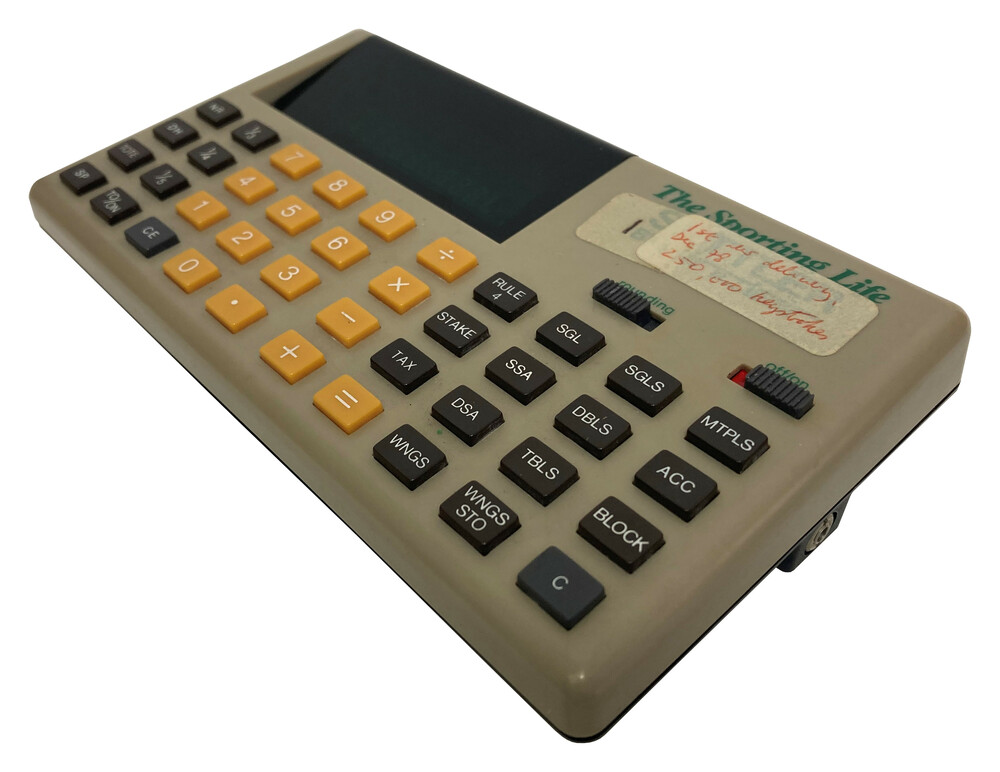

Sinclair Sporting Life Settler, c. 1978

The Sporting Life Settler was a calculator designed for betting shops. It performed complex calculations to determine the winnings of complicated bets on horse and greyhound races.The name came from the newspaper who sponsored the development.

The Sporting Life Settler looks similar to the Sinclair President calculator though fewer were produced as it was more niche. Due to huge competition from Japanese manufacturers and their far more battery-efficient LCD machines, this and the President were manufactured by Radofin in Hong Kong to cut costs.

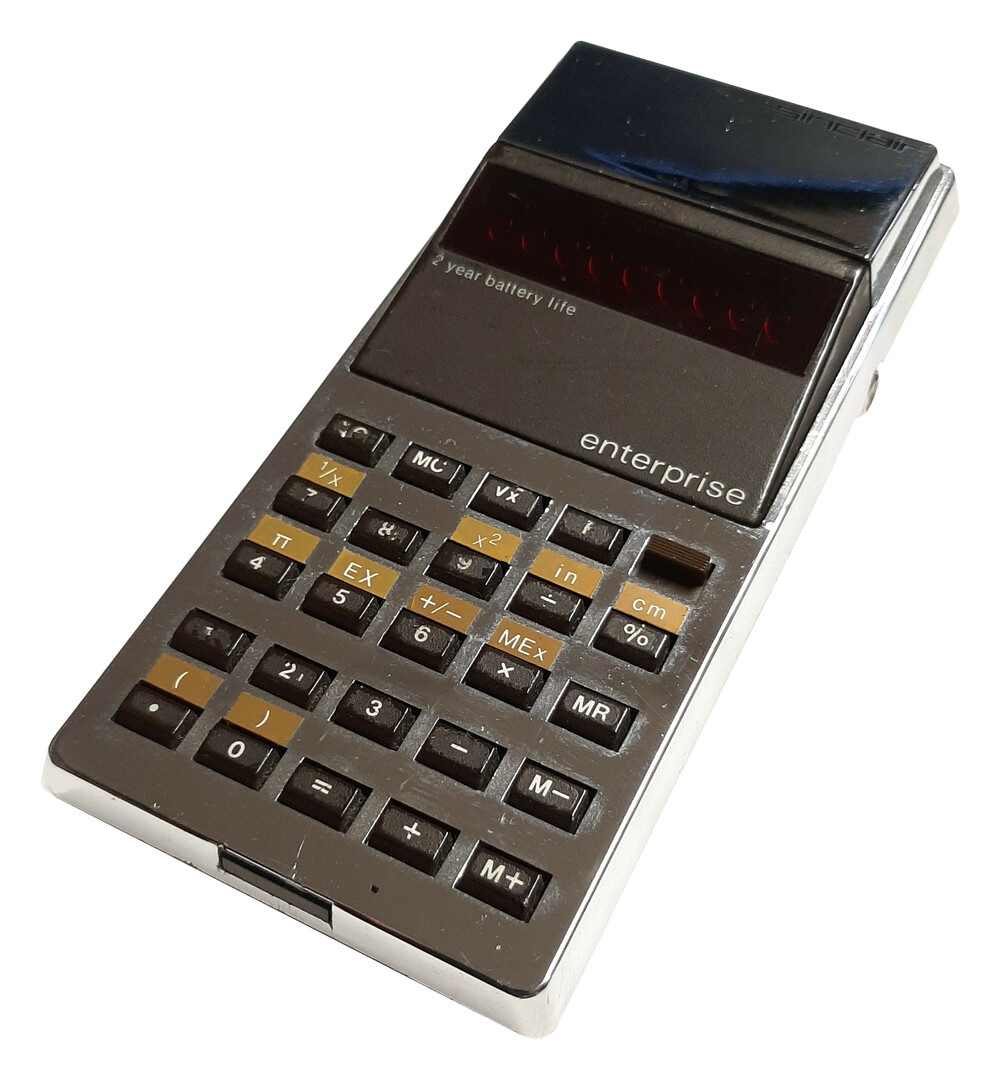

Sinclair Enterprise, Prototype, 1976

A prototype model of the Sinclair Enterprise calculator. This four-function calculator included percentage, memory, and square root functions. Released in October 1977, the following year Sinclair Radionics produced a programmable version.

Image 1: Enterprise Calculator

Image 2: Prototype 1 sticker on inside of case.

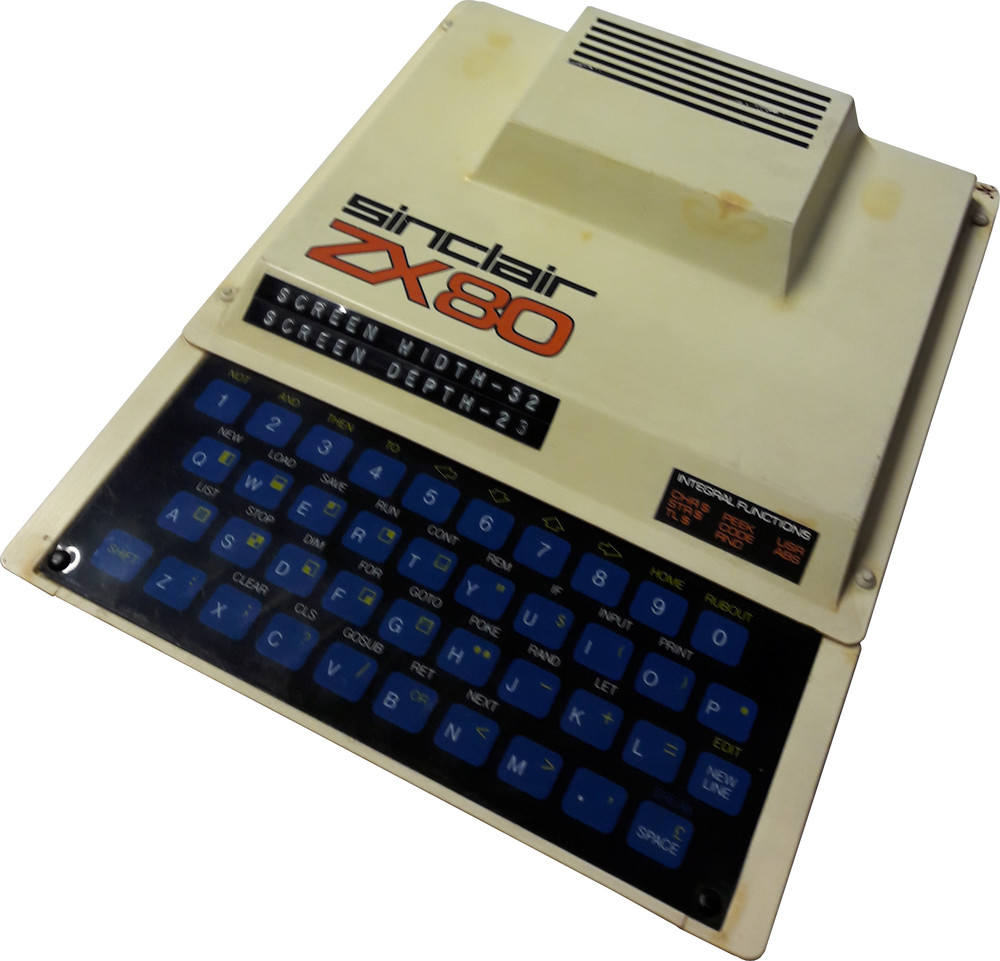

Sinclair ZX80 Prototype, Home Computer, 1980

Released in 1980, the ZX80 was the first computer available in the UK for under £100. You could buy it ready-made or even cheaper as a kit.

The ZX80 was immediately popular. There was a waiting list of several months for both kit and built version.

This example has a basic ROM that reads PDZ4732, an unknown type. It may be that the machine's ROM was installed just before launch to test functionality.

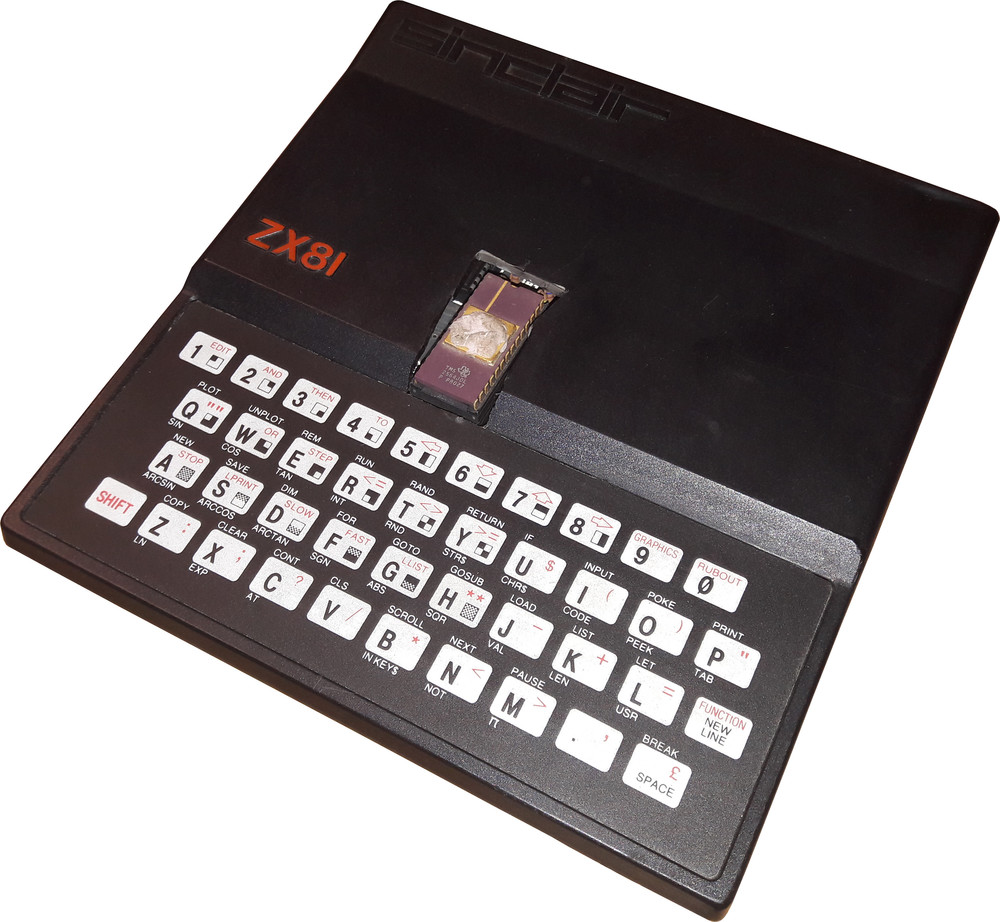

Sinclair ZX81 with Basic EPROM, 1980

This Sinclair ZX81 has close ties with the Sinclair ZX80 8K BASIC machine and was probably manufactured just a few months later. However, the ZX81 case has a cutout to ensure the BASIC ROM would fit and could be easily removed.

Sinclair ZX81 Kit, 1981

You could buy a ZX81 in high-street shops like WHSmith. It was extensively used in schools and colleges for educational purposes. Many people working in the tech industry had their first computer experiences with the ZX81.

Launched on 5th March 1981 by Clive Sinclair as the successor to the ZX80, it was available ready-built (£69.95) or in kit form (£49.95). Its low cost and relative power made it extremely popular. It was also well supported with software and peripherals by both Sinclair and other companies.

Sinclair's advertising claimed that its good design created a higher specification at a lower price. The number of chips was reduced from 21 in the ZX80 to 4 in the ZX81. It was a small machine, weighing 350 grams in total. Designed by Rick Dickinson the in-house industrial designer at Sinclair Research Ltd, the ZX81 won a British Design award.

With only 1K of RAM and 8K of ROM, the ZX81 was not capable of colour graphics. However, this did not stop sales with over 1.5 million units sold.

The ZX81's successor, the ZX Spectrum, was released in April 1982. The ZX81 was discontinued in 1984.

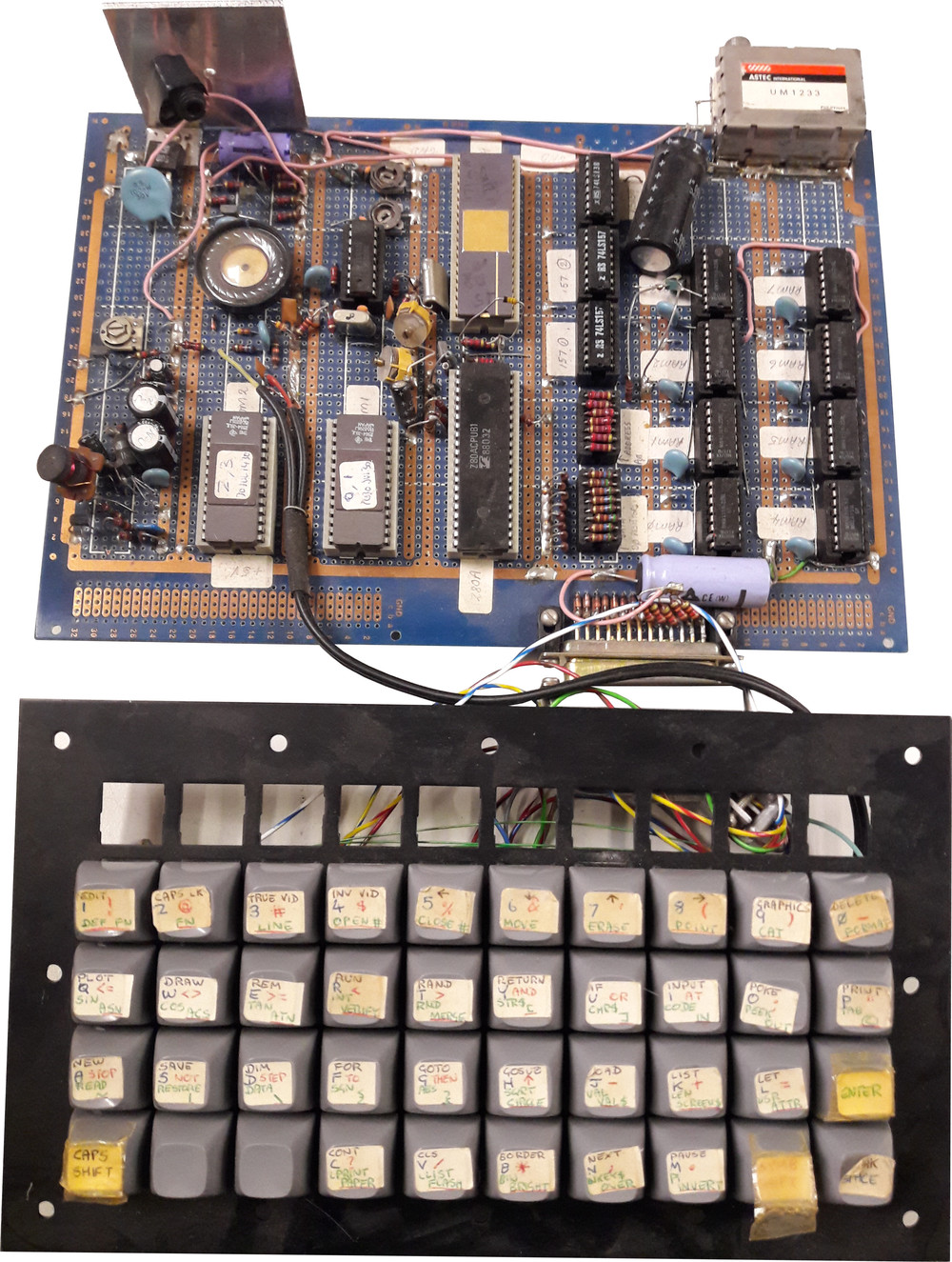

Sinclair ZX Spectrum Prototype, late 1981

The ZX Spectrum played a starring role in the history of personal computing and video gaming. Later fame came at the price of difficult development.

Cambridge company Nine Tiles were subcontracted to produce the Spectrum’s BASIC ROM. They had produced the code for the ZX80 and ZX81 but wanted to rewrite it for the new machine. There was neither the time nor resources, however, and Nine Tiles complained that Clive Sinclair wanted the maximum new facilities for the minimum money. The new BASIC took a year to write and proved to be very slow. Financial disagreements came to a head between Sinclair and Nine Tiles in February 1982. As a result, Sinclair launched the Spectrum with an unfinished ROM.

Nine Tiles continued to work on it until 3 months after the Spectrum's launch, but by then too many machines had shipped. The new code and this prototype were no longer needed.

This prototype has a full travel keyboard with the commands hand written on the top. All the chips are labelled, and the underside of the board is all hand wrap wiring.

The layout has familiar components, but is very different from the Spectrum's final configuration.

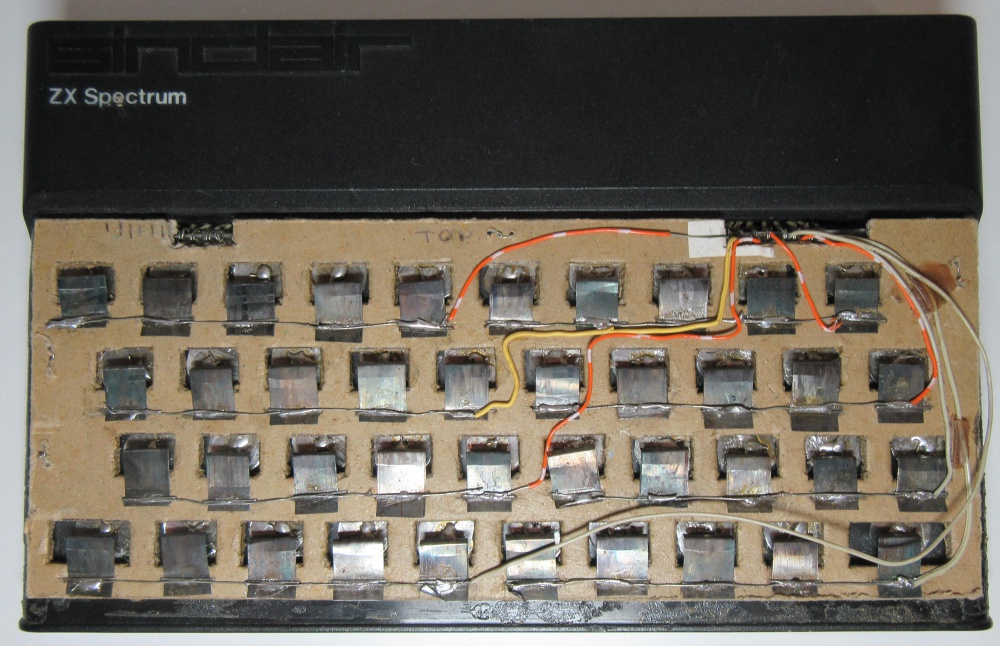

Sinclair Spectrum with Homemade Keyboard

While Sinclair was a pioneer of home-computing so were those who bought his computers. It was evident in the fact the computer kits were as in demand as the fully built examples. This pioneering spirit could be seen here where the keyboard has been replaced by a homemade cardboard and metal example.

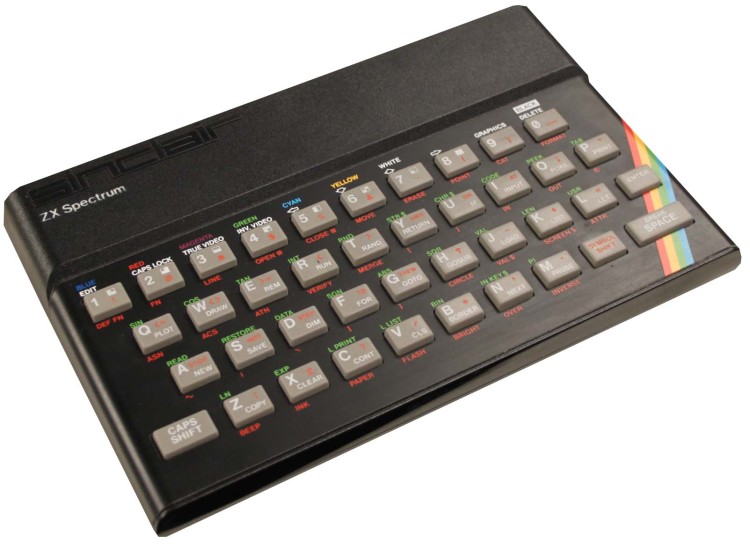

Early Sinclair ZX Spectrum Computer, 1982

Early ZX Spectrums were manufactured with light-grey keyboards, later models with blue-grey keys. Other features of the case reveal more about this particular machine. The white sticker indicates a 48K model, 16K machines had a green sticker. Sinclair Research would regularly repair and upgrade machines. This example has been rewired and had a poorly fitting chip refixed.

Due to high failure rates, it is possible to find issue one boards with blue-grey keys, as Sinclair repaired and rehoused the boards before sending them back to the customer.

Sinclair QL (Property of Sinclair)

This Sinclair QL computer was used in Sinclair's Research & Development department. Stuck on the front right is a 'property of' label.

The machine had its own carrying case and was bicycled around Cambridge to be worked on and demonstrated at various locations including by Sir Clive himself.

Czerweny CZ 1500, 1984

This version of the Spectrum was assembled in Portugal. It is identical to the Timex Sinclair 1500 apart from the label on the front.

Argentinian Sinclair Spectrum, 1982

This version of the Spectrum was assembled in Portugal, but never saw full release. It was intended for the Portuguese and South American markets, with Timex Sinclair branding.

This machine is identical to the Czerweny CZ-2000, which was exported to Argentina.

Some Sinclair branded machines appear to have been exported back to the UK. This example has a sticker for a Plymouth computer supplier.

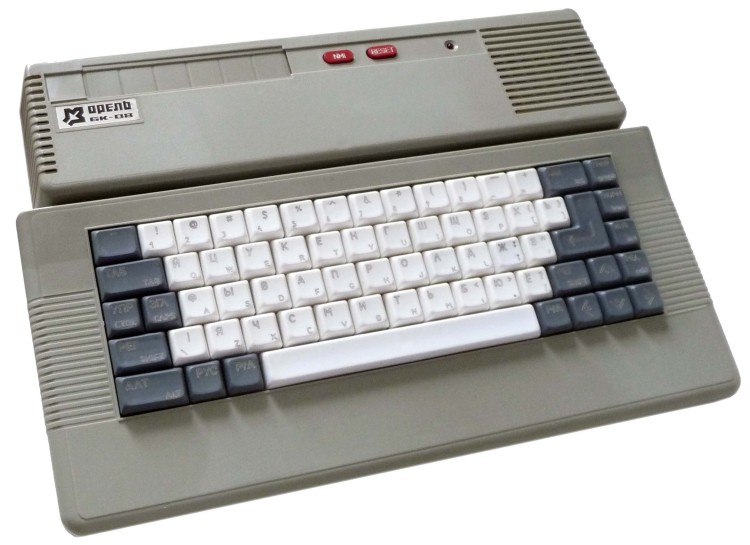

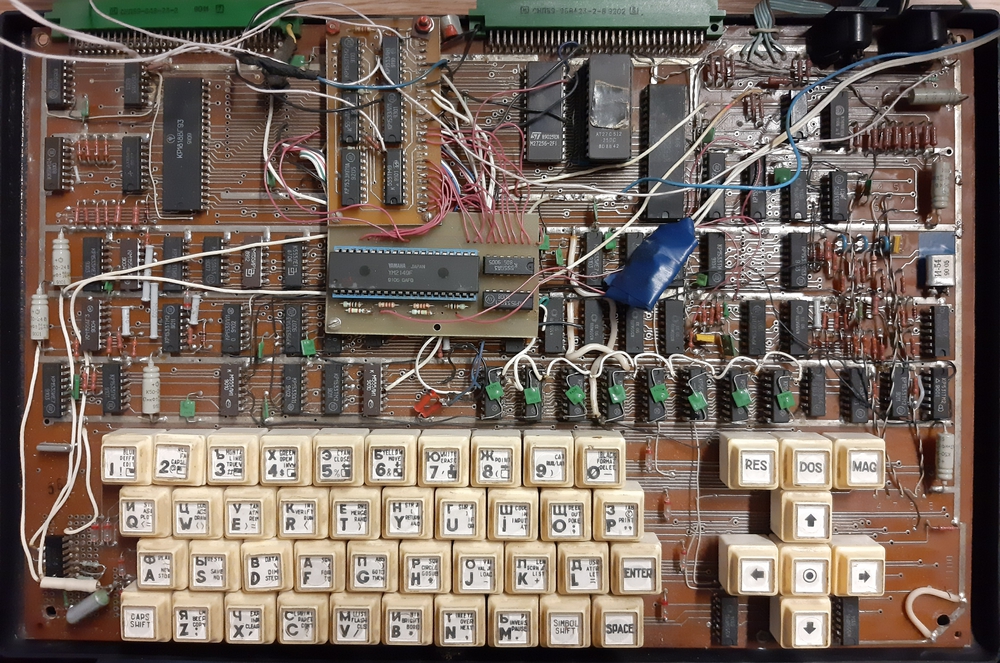

OREL BK-08 - Ukraine Spectrum Clone, 1994

The OREL BK-08 is a personal computer produced in Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine, and fully compatible with the ZX Spectrum. Built around a Z80A-compatible processor, it featured 64KB RAM, a Russian/English keyboard, joystick ports, and a cassette interface. Its most unusual feature is a shadow RAM system with a built-in machine code monitor, activated via a dedicated NMI button—ideal for debugging. The machine booted into a localized BASIC system with Cyrillic support. Despite only partial compatibility with ZX Spectrum software, the BK-08 remains a fascinating example of post-Soviet computing.

Didaktik M - V.D.Skalica Typ U9334, 1990

Released in 1990, the Didaktik M was a redesigned and more reliable alternative to the original Sinclair ZX Spectrum. It featured 48KB RAM, 16KB ROM, improved ergonomics, and a separate arrow key cluster.

A custom chip from Russian firm Angstrem replaced the original ULA, giving the display a square aspect ratio. Though it offered separate joystick ports (Sinclair and Kempston) and an expansion connector, these used non-standard formats. As a result, users across the former Czechoslovakia often built their own quirky, home-made peripherals, adding to the machine’s lasting charm among Eastern European computer enthusiasts.

Kvantor Spectrum Clone, 1988

Built in Severodonetsk, Ukraine by Quantor (НПО "Квантор"), this ZX Spectrum clone arrived at the museum with no documentation. Thanks to online contributors, we now know it’s based on the Kvantor board, likely derived from the popular Leningrad DIY design. It features a 48K/128K mode switch, TR-DOS support, AY sound chip, and multiple DIN connectors for cassette, joystick, and power.

Memory chips are stacked in layers, and the board appears heavily modified with hand-extended circuitry, yet housed in a professionally made case. A hybrid of hobbyist ingenuity and industrial design, it may even be a one-off prototype.

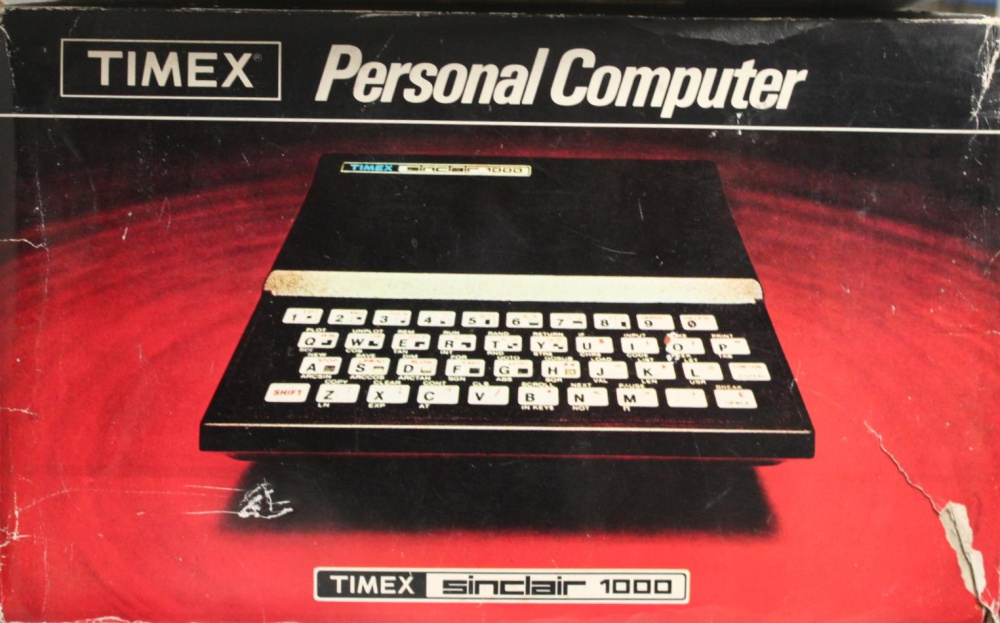

Timex Sinclair 1000

The Timex Sinclair 1000 was the American version of the Sinclair ZX81.

It was created through a joint venture between Timex and Sinclair Research. Launched in 1982, it became the first home computer to sell for under $100. This dramatically widened access to personal computing in the United States.

It featured black-and-white graphics, a membrane keyboard, and just 2KB of memory, with programs saved to cassette tape. The low price sparked a fierce price war with competitors and encouraged countless beginners to experiment with programming, electronics, and hardware add-ons.

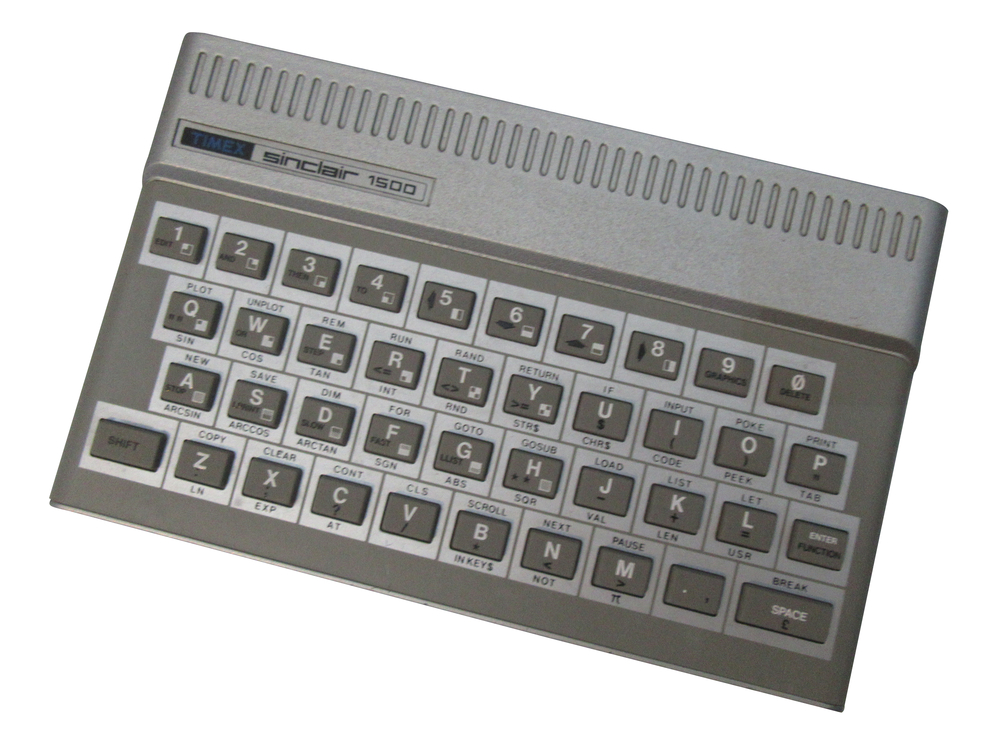

Timex Sinclair 1500, 1982

The Timex Sinclair 1000 was followed by an improved version, the Timex Sinclair 1500, which had more memory (16 KB) and a lower price of US$80. However, the TS1500 did not achieve market success in a market dominated by Commodore, Radio Shack, Atari and Apple.

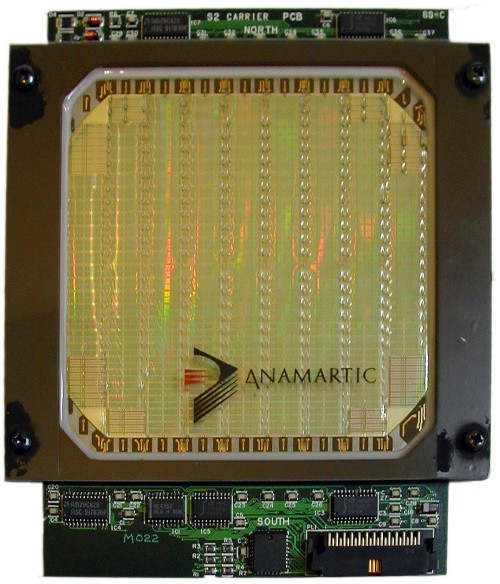

Anamartic Wafer-Scale ... 60MB Solid State Disk, 1989

A 'Wafer Stack' is storage produced made by layering full silicon wafers. Unveiled in 1989 by Anamartic Ltd, this experimental "Wafer Stack" used reprogrammable logic to bypass faulty memory areas. It turns imperfect wafers into reliable high-speed storage. Each 6-inch wafer held 202 memory chips in a spiral layout, continuously self-monitoring and rerouting around failures. With up to eight wafers stacked, it offered capacities of up to 160 megabits—remarkable for the time.

Developed with Fujitsu and championed by Sir Clive Sinclair, the technology promised to revolutionise computers by eliminating chip packaging and waste. Though never commercialised, it foreshadowed today's solid-state drives and wafer-scale computing.

Grundy NewBrain AD, 1982

The NewBrain project started in 1978. Sinclair Radionics began working on a project with Mike Wakefield as designer and Basil Smith as the software engineer. The intention was to compete with Apple. However, when Sinclair realised that the NewBrain could not be made for under £100 he lost interest, failing as it did to meet his focus on inexpensive consumer-oriented products. He turned instead to the ZX80 that was developed by his other company, Science of Cambridge Ltd.

Following the closure of Sinclair Radionics the NewBrain project was moved to Newbury Laboratories by the National Enterprise Board (NEB), the owner of both Sinclair Radionics and Newbury Labs. In 1980 Newbury announced the imminent release of three NewBrain models, including a battery-powered portable computer. In August 1981 Newbury Labs sold the project to Grundy Business Systems.

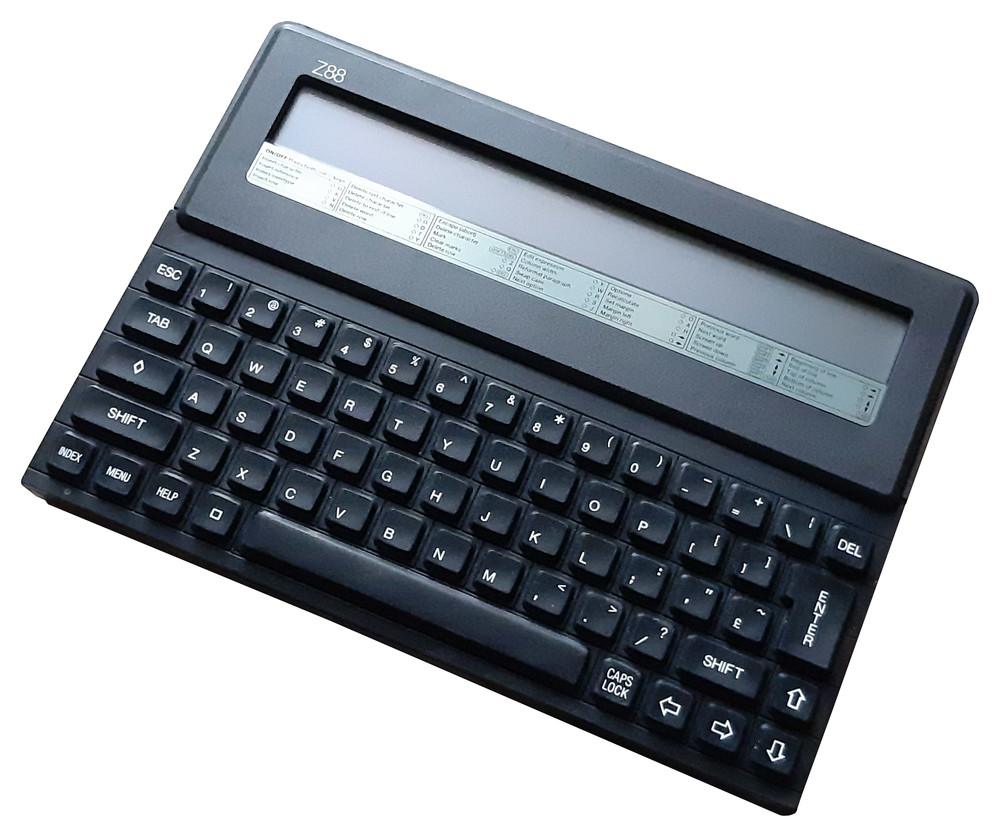

Cambridge Z88, 1987

The machine was conceived by Sir Clive Sinclair and released by his company Cambridge Computer in 1987. Sir Clive was going to market the computer as the Sinclair Z88, but sold the Sinclair name to Amstrad in 1986.

Despite its lightness (the Z88 weighs 0.9 kg) it was surprisingly robust. Its membrane keyboard is almost inaudible, an optional electronic "click" can be turned on if it proves too quiet for the user's taste.

The four AA batteries enables use for 20 hours, while the three memory slots could be be used for RAM expansion, removable mass storage, and proprietary programs.

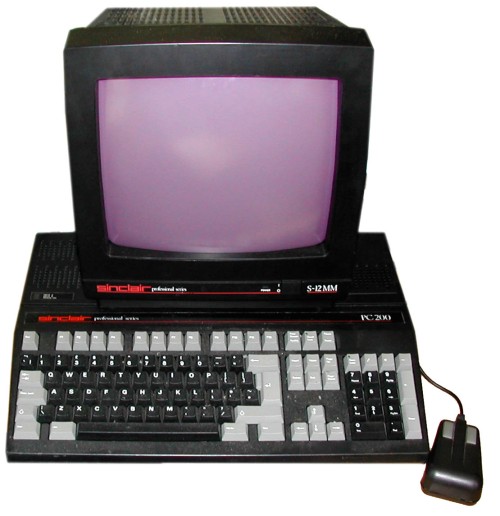

Sinclair PC200, 1988

The PC200 was released by Amstrad in 1988 and was the very last computer branded under the Sinclair name, which was owned by Amstrad at this time. It was a budget computer aimed at business users. Nothing about the PC200 was new. Both computer and monitor were repackaged from earlier products, notably the PC20. The PC200 failed to compete with the more powerful Atari ST and Commodore Amiga and was a commercial failure.

Sinclair C5, 1985

The Sinclair C5 was an electric, one-person, pedal-assisted tricycle. Designed for short-distance travel it was conceived by Clive Sinclair as an affordable, environmentally friendly alternative to cars. The C5 had a top speed of 15 mph (24 km/h) and a range of around 20 miles (32 km) per charge. It was powered by a 12-volt electric motor all housed in a lightweight body.

Despite its forward-thinking approach, the C5 was met with criticism for its safety in traffic, and limited performance. 14,000 units were produced with sales falling far short of expectations.

The C5 has since gained cult status. A pioneering attempt at mainstream electric transport, foreshadowing the micro-mobility revolution seen today.

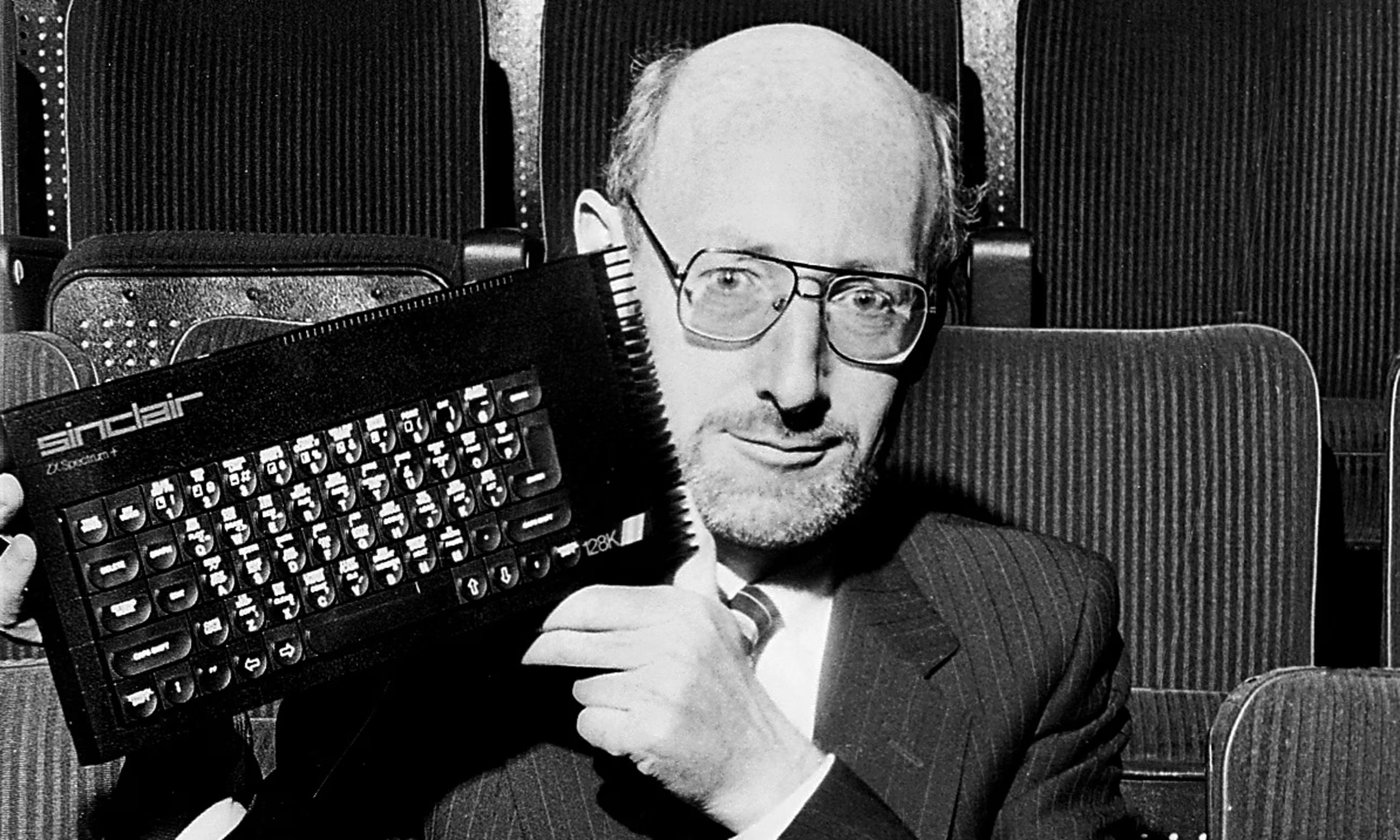

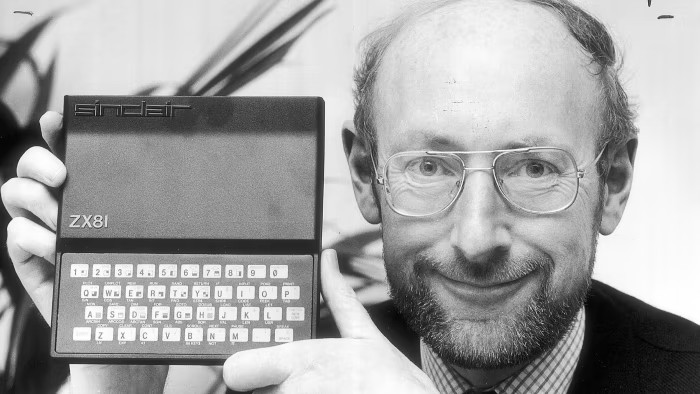

Clive Sinclair: A Very English Disruptor

Centre for Computing History

Sir Clive Sinclair was an English maverick. He was pioneering in wearable tech, electric vehicles and personal computing. Sinclair introduced a generation from across the globe to programming. Yet his career is as much remembered for its commercial failures as it is his visionary ideas. He is not as well remembered as his Silicon Valley counterparts.

Born in 1940, Sir Clive Sinclair began his career as a technical journalist before founding Sinclair Radionics in 1961. From his Cambridge base, he built a reputation for creating affordable, compact consumer electronics. From pocket radios and calculators to the world’s first slimline pocket TV he was always at the forefront of good design and miniturisation.

In the 1980s, Sinclair became a household name as his ZX series of home computers brought digital technology into millions of homes, inspiring a new generation of programmers and gamers.

Sinclair brought joy and accessibility to home computing. His later ventures showed the same restless curiosity. Much like today’s tech disruptors, Sinclair thrived on high-risk ideas, forever pushing the boundaries of what technology could achieve.

Exhibition Quiz:

Can you tell your Spectrums from from your C5s?...